Published in Huffington Post, Us Edition.

Not one day goes by without hearing about predictions

of massive job losses due to « Uberisation ». However, statisticians find it hard to read the effect

of said Uberisation outside of a very narrow set of sectors (car

transportation, rental of apartments, etc.). Furthermore micro-economic studies

tell a quite different story for sectors outside this set. In manufacturing

[1], for example, the way production adapts to new technologies is very slow

and incremental. Productivity gains may indeed have many causes, such as additive

manufacturing (“3D printing »), increased digitization of processes made

possible by the price drop of sensors and of information processing, or a simply

better organization of the manufacturing chain. As a consequence, each year,

industrial productivity naturally increases by a few percentage points, even in

the absence of any technological/business model disruption. Actually if

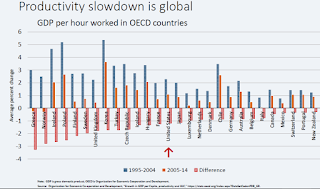

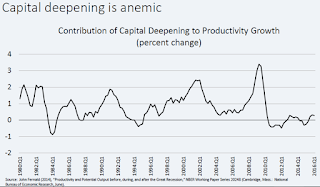

something new is happening in the industrial sectors it is rather a deceleration

in productivity gains and productivity investments rather than an acceleration!

of massive job losses due to « Uberisation ». However, statisticians find it hard to read the effect

of said Uberisation outside of a very narrow set of sectors (car

transportation, rental of apartments, etc.). Furthermore micro-economic studies

tell a quite different story for sectors outside this set. In manufacturing

[1], for example, the way production adapts to new technologies is very slow

and incremental. Productivity gains may indeed have many causes, such as additive

manufacturing (“3D printing »), increased digitization of processes made

possible by the price drop of sensors and of information processing, or a simply

better organization of the manufacturing chain. As a consequence, each year,

industrial productivity naturally increases by a few percentage points, even in

the absence of any technological/business model disruption. Actually if

something new is happening in the industrial sectors it is rather a deceleration

in productivity gains and productivity investments rather than an acceleration!

The issue is therefore not to brandish the digital

threat some gurus and consultants like to evoke, but rather to understand the

nature of such threat to the existing organization of a given value chain. In

many cases, the threat is more likely to come from a competitor – who may be

quicker than you in using digital in order to increase performance, or to propose

innovative services – instead of an Internet giant or a start-up popping up out

of the blue. There is real risk of investing too much to counter a theoretical Uberisation,

and there is also real risk in not investing enough to reinforce your own

productivity and quality of service. These poor investment choices, fueled by hazardous

extrapolations and narratives, brings either inspiring optimism to investors or

fears to businesses. That is precisely the definition a bubble [2].

threat some gurus and consultants like to evoke, but rather to understand the

nature of such threat to the existing organization of a given value chain. In

many cases, the threat is more likely to come from a competitor – who may be

quicker than you in using digital in order to increase performance, or to propose

innovative services – instead of an Internet giant or a start-up popping up out

of the blue. There is real risk of investing too much to counter a theoretical Uberisation,

and there is also real risk in not investing enough to reinforce your own

productivity and quality of service. These poor investment choices, fueled by hazardous

extrapolations and narratives, brings either inspiring optimism to investors or

fears to businesses. That is precisely the definition a bubble [2].

Not all sectors are affected in the same way. In

transportation, Uber “disrupts” the « interaction » jobs (which are

about the relation between a cab and a customer), not the

« production » jobs (Uber does not decrease the number of people driving

a car). The “design” jobs (management, design, artists…) are still far from

being disrupted: at best, artificial intelligence provides them with tools

eliminating a small and repetitive part of their job. In the case of Uber,

interaction and production jobs are complement, not substitutes: the lower the

cost and the complexity of the former, the more plentiful the latter. Cab

companies owners, call centers operators, and taxi licenses owners can indeed

worry about Uberisation. But drivers shouldn’t as Uberisation leads to a net increase

in the number of driver jobs, and this is a net gain for society as a whole

after taking into account customers’ surplus in the tally. Please also note

that we’re still very far from the driverless cabs – plane “autopilots” have

been existing for years, and they still need a human supervision.

transportation, Uber “disrupts” the « interaction » jobs (which are

about the relation between a cab and a customer), not the

« production » jobs (Uber does not decrease the number of people driving

a car). The “design” jobs (management, design, artists…) are still far from

being disrupted: at best, artificial intelligence provides them with tools

eliminating a small and repetitive part of their job. In the case of Uber,

interaction and production jobs are complement, not substitutes: the lower the

cost and the complexity of the former, the more plentiful the latter. Cab

companies owners, call centers operators, and taxi licenses owners can indeed

worry about Uberisation. But drivers shouldn’t as Uberisation leads to a net increase

in the number of driver jobs, and this is a net gain for society as a whole

after taking into account customers’ surplus in the tally. Please also note

that we’re still very far from the driverless cabs – plane “autopilots” have

been existing for years, and they still need a human supervision.

In order to estimate the overall impact of Uberisation

on employment, we used micro-level employment data broken down across 88 industries

(retail, metallurgy, publishing, and building construction …) and across different

functions (production, interaction and design). This data is available for

France, but there is no reason why the results would be significantly different

elsewhere. In our model, « production » and « design » activities are affected

by productivity gains (use of machines, robots for production, artificial

intelligence…) but they don’t disappear entierely. We show that “interaction” jobs

may however be replaced entirely by the Uberisation process.

on employment, we used micro-level employment data broken down across 88 industries

(retail, metallurgy, publishing, and building construction …) and across different

functions (production, interaction and design). This data is available for

France, but there is no reason why the results would be significantly different

elsewhere. In our model, « production » and « design » activities are affected

by productivity gains (use of machines, robots for production, artificial

intelligence…) but they don’t disappear entierely. We show that “interaction” jobs

may however be replaced entirely by the Uberisation process.

Our analysis was completed using industry experts’

assessments, we also took into account the dynamics of demand. For example, healthcare services are

expected be digitized, but the increasing structural demand for such services ensures

that, in the long run, there is no risk of a decline

in employment.

assessments, we also took into account the dynamics of demand. For example, healthcare services are

expected be digitized, but the increasing structural demand for such services ensures

that, in the long run, there is no risk of a decline

in employment.

Our model estimates that, in the medium term, 14 % of

the total employment could be displaced by digital. This can of course just be an

order of magnitude, but it is consistent with other studies (for the same

country, OECD’s estimate is 9%)[4].

the total employment could be displaced by digital. This can of course just be an

order of magnitude, but it is consistent with other studies (for the same

country, OECD’s estimate is 9%)[4].

It shows that the reality is very far from the scary

situation where all jobs are eaten away by robots powered by artificial

intelligence. It quantifies a reality: some jobs are indeed made redundant by

digital, and they are the ones the most visible – the « interaction »

jobs (sales staff, call centers…). But millions of « production »

jobs (construction, garbage collection,…) are hardly affected. Industrial

jobs do indeed see annual productivity gains, but the size of such gains has

been decreasing, not increasing, in the last decade.

situation where all jobs are eaten away by robots powered by artificial

intelligence. It quantifies a reality: some jobs are indeed made redundant by

digital, and they are the ones the most visible – the « interaction »

jobs (sales staff, call centers…). But millions of « production »

jobs (construction, garbage collection,…) are hardly affected. Industrial

jobs do indeed see annual productivity gains, but the size of such gains has

been decreasing, not increasing, in the last decade.

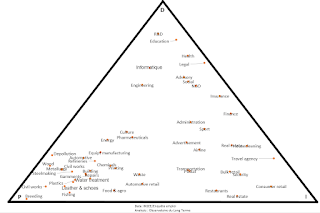

Structure of the jobs by

industry

industry

This figure represents the

structure of the jobs of each industry in the economy. The position of each

industry relative to the vertex “I”, “P” and “D” represents the share of

Interaction, Production and Design jobs in this industry. For example,

industries with 100% of Interaction jobs would be represented in the vertex “I”

and industries with equal shares of Interaction, Production and Design jobs

would be represented at the center of the triangle. Based on the study

mentioned in this article, the closer to the vertex “I”, the more menaced for

“Uberisation”.

structure of the jobs of each industry in the economy. The position of each

industry relative to the vertex “I”, “P” and “D” represents the share of

Interaction, Production and Design jobs in this industry. For example,

industries with 100% of Interaction jobs would be represented in the vertex “I”

and industries with equal shares of Interaction, Production and Design jobs

would be represented at the center of the triangle. Based on the study

mentioned in this article, the closer to the vertex “I”, the more menaced for

“Uberisation”.

Our model also reveals some winning sectors. They are

the ones complementary to interaction jobs: the simpler and the cheaper the

interactions, the more customers will consume services sold through theses

interactions. Farmers are already experiencing a maximum level of competitive

pressure from purchasing groups. An Uber for fruit and vegetables (which would

be delivered directly to customers) could hardly reduce their margins even

more. On the other hand, it could allow customers to raise the level of quality

and increase the farmer’s revenues. As mentioned above, a decrease in

interaction costs will lead to an increase in production demands – efficiency

gains are not “lost”, but reallocated somewhere. Finally, the economy is not

inert: in France, 15% of all jobs are destroyed every year and the same

percentage are created because of evolutions related to technology (more renewable

energy jobs and less jobs related to coal), competitiveness (exchange rate

variations, know-how development…) or consumer tastes (more e-cigarette and

less mobile phone shops). The impact of Uberisation (14% of employment over

several years) is not much compared to Schumpeterisation (15% of employment each

year)!

the ones complementary to interaction jobs: the simpler and the cheaper the

interactions, the more customers will consume services sold through theses

interactions. Farmers are already experiencing a maximum level of competitive

pressure from purchasing groups. An Uber for fruit and vegetables (which would

be delivered directly to customers) could hardly reduce their margins even

more. On the other hand, it could allow customers to raise the level of quality

and increase the farmer’s revenues. As mentioned above, a decrease in

interaction costs will lead to an increase in production demands – efficiency

gains are not “lost”, but reallocated somewhere. Finally, the economy is not

inert: in France, 15% of all jobs are destroyed every year and the same

percentage are created because of evolutions related to technology (more renewable

energy jobs and less jobs related to coal), competitiveness (exchange rate

variations, know-how development…) or consumer tastes (more e-cigarette and

less mobile phone shops). The impact of Uberisation (14% of employment over

several years) is not much compared to Schumpeterisation (15% of employment each

year)!

There is no doubt that digitization will reduce the

number of jobs in some sectors and increase it elsewhere. With each technological

wave, there are risks for some jobs categories, but also opportunities for jobs

and value creation. It is better to start with factual and realistic numbers in

order to better deal with such risks and grasp such opportunities.

number of jobs in some sectors and increase it elsewhere. With each technological

wave, there are risks for some jobs categories, but also opportunities for jobs

and value creation. It is better to start with factual and realistic numbers in

order to better deal with such risks and grasp such opportunities.

Vincent Champain, senior executive in a multinational

company and president of the Long Term Observatory think tank, and Frederic

Benque, investment partner at

NextWorld. Many thanks to Joyce Bessis for her help on the

translation.

company and president of the Long Term Observatory think tank, and Frederic

Benque, investment partner at

NextWorld. Many thanks to Joyce Bessis for her help on the

translation.

[2] Definition of Professor Robert Schiller, expert on

bubbles in « Rising Anxiety That Stocks Are Overpriced », New York Times,

27/8/2015.

bubbles in « Rising Anxiety That Stocks Are Overpriced », New York Times,

27/8/2015.

[3] Employment Study 2013, Data from INSEE