time in Brazil, the world is looking to Brazil with enthusiastic eyes since it

will be hosting soon the World Cup and the Olympics in 2016 that seems as

recognition of its ascending influence in the international markets.

it has many reasons to celebrate. The

country has made remarkable economic and social progress in the last decade. It

has raised 22 million people out of poverty since 2003 and built a stable

economy. It fought successfully against the big scary ghost from its past, the

hyperinflation, by granting autonomy to its Central Bank that in turn,

implemented the inflation targeting during president Fernando Henrique Cardoso

government (1995-2002) which drove annual inflation down from 916,46% in 1994

to 5,97% in 2000 and by creating the Law of Fiscal Responsibility that sought

to control municipal and states expenses and promote more transparence in

public spending. It’s an economy with full-employment (unemployment rate of

5,5%, OECD Economic Surveys Brazil, October 2013) and strong internal

consumption. Moreover, many state-owned companies were privatized and

flourished as a result of being allowed to operate at arm’s length from the

government and became strong global players as Vale, a mining giant and

Embraer, an aircraft-maker.

Brazil has not seemed to have done all his homework to boost economic

development. Three years of weak growth shows clearly that Brazil needs to

review its economic model. In the last “Global Competitiveness Report

2012-2013” released by the World Economic Forum, structural reforms were cited as

the main pillars to drive productivity and competitiveness. And it seems that

Brazil is not following the guidelines as we would expect from a country that

wants to sustain its economic growth in the long-term.

The first pillar is

government attitudes toward markets and its capability of maintaining an

efficient management of its operation. In Brazil, there is a lack of

transparence and trustworthiness in the government. This can be illustrated by

an incident that was in the international press recently, the case of the OGX,

a company engaged in the oil & gas exploration and production, that was one

of the most negotiated stocks in Brazil, it appreciated 78,94% 4 years after

its IPO and now its stock worth last than 0,1 €. This was a consequence of a

company that was highly leveraged and promised unrealistic potentials for its

reserves, revealing a regulatory bottleneck that enabled a CEO from a public capital

company to make excessive statements which in the end damaged many investors.

Furthermore, there is an excess of government intervention in the economy. The

government created a cap for electricity prices in 2012, aiming to reduce

overall production costs in the economy and control inflation. Nonetheless, instead,

these new terms of the concessions caused several of Brazil’s largest power

companies to suffer significant decreases in profitability and investors

experienced a long-lasting detrimental effect on shareholder value – which will

probably cause underinvestments for the future. Also, as an anti-inflationary

measure, the government forced Petrobras, a mixed capital oil company, to hold

down the price of petrol, which in turn, made it had losses of US$ 1,1 billion

from January to October 2013, as it was importing oil at a higher price than it

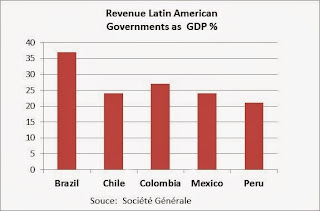

sold on the domestic market. In addition, the tax burden is extremely high,

between 2010-2013, the government revenue weighted 37% of its GDP, much higher

than its Latin America counterparts (chart below):

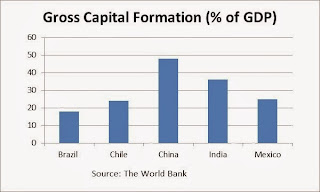

other pillar is infra-structure and the absence of a rebound in investment

(currently at 19% of GDP) reflects the current challenge to rebalance the

economy and maintain the country’s economic growth. We can observe in the

following chart that the level of Gross Capital Formation as a % of GDP

(average 2009-2013) is lower than in other emerging countries:

The country

dealt pretty well with the global financial crisis of 2007/2008 achieving a GDP

growth rate of 7,53% in 2010. This achievement was based on its good

macroeconomic stability but it was also a consequence of China growing at

fantastic rates and being hungry for Brazilian commodities. In addition, there

was a sluggish America that was seeking

for the Emerging markets risk premium. Nonetheless, the international economic

scenario changed. But is it sustainable? Maybe not, according to Israel Malkin

and Mark Spiegel from the Federal Reserve of San Francisco, China is facing a

“middle-income trap” in which rising wages erode global competitiveness,

leading to a marked slowdown. Furthermore, the US

investors might reduce their exposition to the Emerging Markets as the Fed

reduces its asset buying programs and besides, the American stock market is

enjoying an uptrend.

development from now on?

answer is more political: these reforms will not come until voters value policies

that will generate good results in the long-term. We already could observe that

a combination of slower growth and an assertive new middle class is forcing

political change. Brazilians are tired

of a system which has a Scandinavian tax burden and a third world country

public services. A country which is serious about a long-term solution should

improve the level of education and create a plan to fills the current

infrastructure gaps. A model that only

stimulates the consumption is clearly not a long-term solution, on the other

way around, it can imposes deep problems as the country can face higher inflation

due to an internal supply that no longer satisfies the demand and an increase

in its current account deficit as the country will need to import more to

respond to gaps in the supply side.

tackle those constrains, as offering higher returns for investors to persuade

them to build a US$ 93 billion of infrastructure on road projects, ports and

rails works. During the 2000’s France enjoyed a high growth, reducing

unemployment but failed to undertake structural reforms (pensions, labor

market, tax level & structure, public spending…). Unsurprisingly, these

reforms proved much harder a few years later. Brazil has to take advantage of its

current phase of low unemployment and rising real incomes to tackle its missing

points in order to jump-start economic growth.